Persistent Virus in Long Covid:

The Emerging Science

Understanding the concept of a persistent virus in Long Covid

Long Covid, or Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC), describes symptoms such as fatigue, breathlessness and brain fog that persist for months after the initial infection has cleared.

Among several hypotheses proposed to explain this, one has become increasingly compelling: the Persistent Virus Hypothesis. It suggests that remnants of SARS-CoV-2, viral RNA, proteins, or even small populations of active virus, may persist in body tissues. These residual viral elements can continue to stimulate the immune system, causing chronic inflammation and ongoing symptoms.

Research groups at institutions such as Harvard Medical School, Mayo Clinic, Stanford University, Yale School of Medicine, King’s College London, and the NIH RECOVER Initiative are all investigating this possibility.

This page summarises what is currently known, explores Attomarker’s findings on immune endotypes, and explains how this understanding may one day help to personalise treatment for people with persistent symptoms.

Evidence for viral persistence in Long Covid

The science is evolving, but growing data support the probability that SARS-CoV-2 may not always be completely eliminated after acute infection.

Findings across multiple studies include:

Chertow D. et al., Cell (2022):

SARS-CoV-2 RNA and proteins detected in multiple tissues up to 230 days after infection.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0092867422014266

Patterson B.K. et al., Frontiers in Immunology (2021):

Spike protein found persisting in circulating monocytes in people with post-acute COVID.

https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2021.746021/full

Zollner A. et al., Gut (2022):

Viral antigen persistence in the gut associated with ongoing immune activation.

https://gut.bmj.com/content/71/12/2263

Mass General Brigham (2023):

Persistent viral proteins detected in blood of Long Covid patients.

https://www.massgeneralbrigham.org/en/about/newsroom/press-releases/study-finds-persistent-infection-could-explain-long-covid-in-some-people

Although not yet definitive proof, these studies together indicate that persistent viral material, and the immune system’s continued response to it, may explain many of the chronic effects seen in persistent virus Long Covid.

Persistent virus – now a probability, not a possibility

The evidence that SARS-CoV-2 can persist in the human body for months after acute infection has grown steadily. What began as an intriguing hypothesis is now considered a probable and significant contributor to Long Covid pathophysiology.

More than a dozen peer-reviewed studies have demonstrated the presence of viral RNA, proteins or antigens in tissues long after patients test negative on conventional PCR tests. Together they confirm that the virus can linger in multiple organs and systems.

However, the field remains emergent.

While persistence itself is now widely accepted, the mechanisms by which residual viral material drives the diverse symptom patterns of Long Covid are less clearly mapped. Some patients may experience direct tissue effects from ongoing viral replication, while others appear to have immune dysregulation, endothelial damage or autoimmune responses triggered by lingering antigens rather than live virus.

Researchers agree on three key points:

Persistence is real:

SARS-CoV-2 can remain in human tissues well beyond the acute phase.

Mechanisms are multifactorial:

Persistent virus may act through chronic immune stimulation, microclot formation, autonomic dysfunction or secondary viral reactivation.

Individual variation is large:

Different people show different persistence sites, immune patterns and symptom clusters — explaining the complexity of Long Covid presentations.

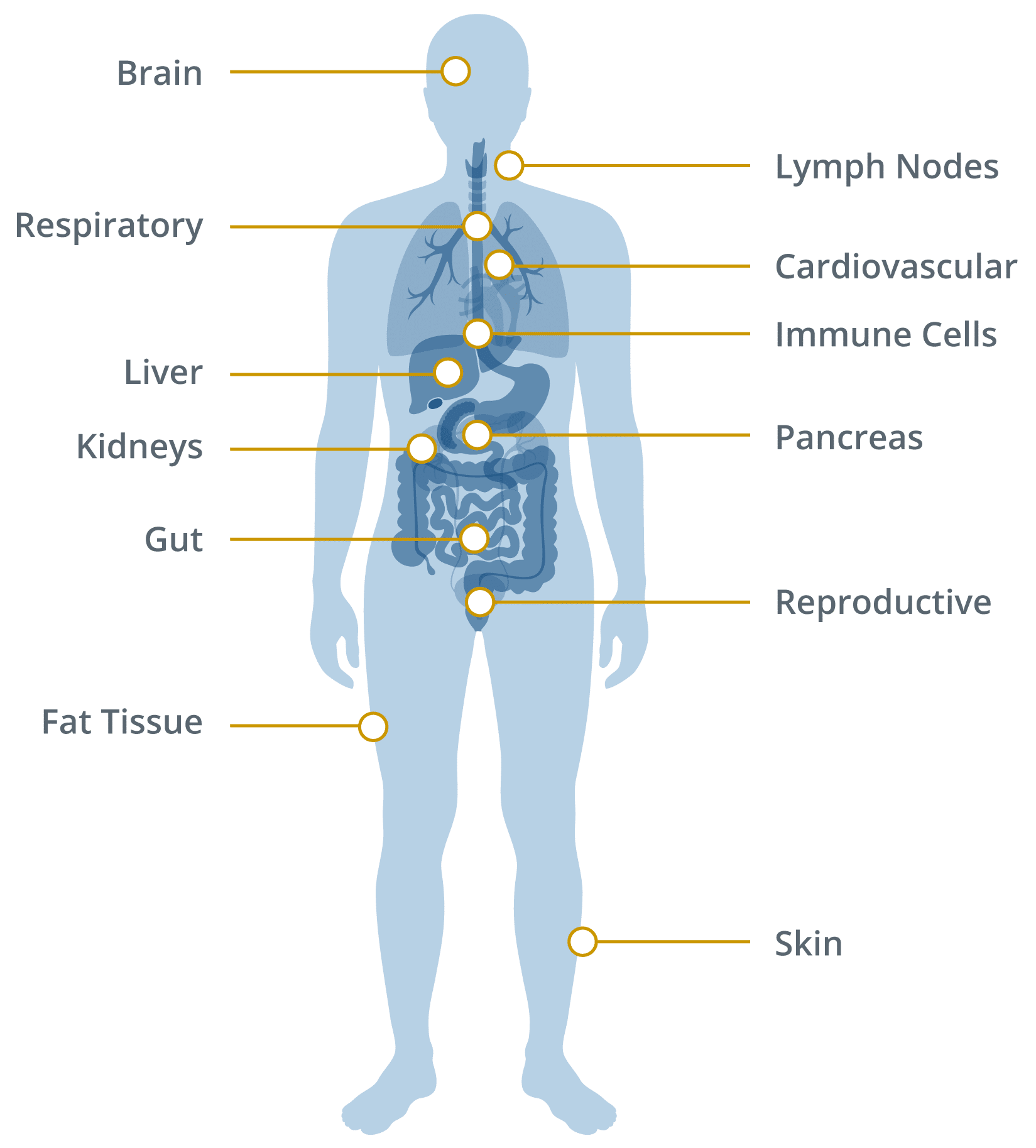

Where and how the virus might persist

The virus appears capable of surviving in areas of the body with lower immune surveillance, where it can remain unnoticed yet continue to provoke an immune response.

Evidence of persistence has been found in:

Gastrointestinal tract:

Viral RNA and antigens detected in intestinal tissue months after recovery.

Immune cells:

Monocytes and macrophages may contain viral proteins, sustaining inflammation.

Lymphatic tissue:

Viral material identified in lymph nodes and spleen.

Nervous system:

Viral remnants reported in olfactory tissue and brainstem.

Adipose tissue:

Possible storage of viral components in fat cells.

These reservoirs could act as chronic sources of immune activation even after acute infection has resolved.

Comprehensive list: where SARS-CoV-2 has been shown to persist

Below is a structured list of organ systems and tissue sites with evidence of viral persistence or antigen detection, supported by published studies.

Areas SARS-CoV-2 has Been Found to Linger

Immune endotypes: new insight into why some people remain unwell

Attomarker’s multiplex antibody research has shown that Long Covid may be associated not only with viral persistence but also with distinct immune-response patterns, called endotypes.

An immune endotype describes how a person’s immune system has responded to infection or vaccination, reflected in the quantity and quality of antibodies across multiple SARS-CoV-2 variants.

Through analysis of hundreds of samples, Attomarker’s studies have found that about 60 to 65 percent of people with Long Covid show an immune endotype characterised by either insufficient antibody levels or low-quality (poorly binding) antibodies to one or more variants.

Why immune gaps might explain persistent symptoms

If immunity is incomplete, residual viral particles may survive in protected tissues. This allows the virus or its antigens to remain active and provoke inflammation over time.

Possible sequence:

Incomplete immunity allows residual viral particles to survive in niche tissues.

Persistent viral presence drives ongoing immune activation and inflammation.

Chronic inflammation manifests as the prolonged symptoms of Long Covid.

An over-reactive or hyper-immune endotype may instead cause excessive antibody activity and self-reactivity, leading to autoimmune-like symptoms even when no virus remains.

Towards personalised approaches: filling the immune gaps

Attomarker is collaborating with research partners to study how these immune gaps might be addressed through personalised immunological strategies. The goal is to strengthen gaps identified in an individual’s antibody spectrum with interventions tailored to that pattern.

Approaches under exploration include:

Targeted vaccination that stimulates antibodies covering missing variant responses.

Monoclonal antibody therapies that provide temporary coverage for absent immune responses.

Adjunctive immune support that enhances antibody quality or binding strength, known as avidity.

Ongoing research and clinical trials

Research into persistent virus Long Covid is expanding globally. Several large programmes are underway to understand viral reservoirs, immune dysregulation and therapeutic options.

NIH RECOVER Initiative (US):

A nationwide study examining biological causes of Long Covid, including viral persistence and immune endotypes.

https://recovercovid.org

Mass General Brigham and Brigham and Women’s Hospital (US):

Investigating viral protein persistence and inflammatory markers.

https://www.massgeneralbrigham.org/en/about/newsroom/press-releases/study-finds-persistent-infection-could-explain-long-covid-in-some-people

King’s College London (UK):

Studying viral antigen persistence and symptom duration.

https://www.kcl.ac.uk

University of Exeter / Attomarker (UK):

Examining antibody spectrum endotypes and immune quality as predictors of Long Covid persistence.

https://attomarker.com/confronting-long-covid-the-persistent-virus-hypothesis

Therapeutic implications of the persistent virus hypothesis

Understanding the biological mechanisms of persistence is guiding early studies of new interventions.

Current areas of exploration:

Antivirals:

Testing whether suppressing residual virus with agents such as nirmatrelvir or ritonavir (Paxlovid) improves symptoms.

Immunomodulators:

Agents that calm excessive immune activation or restore immune balance.

Gut microbiome restoration:

Treatments to heal the intestinal barrier and rebalance flora where viral antigens are detected.

Vascular and microclot therapies:

Approaches that resolve clotting abnormalities possibly driven by chronic viral stimulation.

Personalised vaccination strategies:

Adjusting booster type and timing to address endotype-specific antibody gaps.

A balanced view of the science

The persistent virus hypothesis is one of several explanations for Long Covid. Other mechanisms under investigation include autoimmunity, reactivation of latent viruses such as Epstein–Barr virus, and metabolic or mitochondrial dysfunction.

It is increasingly clear that multiple mechanisms interact, and different individuals may have different biological drivers.

By identifying immune endotypes and mapping antibody spectra, researchers aim to connect these mechanisms, linking viral persistence, immune dysfunction and symptom pattern into a coherent scientific model.

References and further reading

Chertow D. et al. “Persistence of SARS-CoV-2 in multiple tissues up to 230 days after infection.” Cell (2022).

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0092867422014266

Patterson B.K. et al. “Persistence of Spike Protein in Monocytes of Patients with Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19.” Frontiers in Immunology (2021).

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2021.746021/full

Zollner A. et al. “SARS-CoV-2 antigen persistence in the intestine.” Gut (2022).

https://gut.bmj.com/content/71/12/2263

NIH RECOVER Initiative. “Viral persistence, reactivation and mechanisms of Long COVID.”

https://recovercovid.org/publications/viral-persistence-reactivation-and-mechanisms-long-covid

Shaw A.M. et al. Attomarker / University of Exeter. “Identification of immune-response endotypes in Long Covid.”

https://attomarker.com/confronting-long-covid-the-persistent-virus-hypothesis

Mayo Clinic. “COVID-19 long-term effects.”

https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/coronavirus/in-depth/coronavirus-long-term-effects/art-20490351

Mass General Brigham. “Persistent infection could explain Long Covid in some people.”

https://www.massgeneralbrigham.org/en/about/newsroom/press-releases/study-finds-persistent-infection-could-explain-long-covid-in-some-people

COVID Antibody Spectrum Test

Authorised under UKCA

Advanced multiplex test that measures antibody quantity and quality across 15 COVID-19 variants to provide an informative window into the immune system of Long COVID patients, including classification of their endotype into hypoimmune, hyperimmune or universal responder. This can help guide appropriate and personalised therapeutic choices.

Authorised under UKCA

Quantitative measurement of antibody levels

Quantitative assessment of antibody functional quality

Identifies immune subtypes

Supports informed treatment & vaccination decisions