Understanding Endotypes in Long Covid

What is an Endotype

In medicine, conditions that look similar on the surface can often arise from very different biological processes underneath. To describe these internal differences, scientists use the term endotype.

An endotype is a biologically defined subtype of a disease or condition. It describes what is happening inside the body at a molecular or immune level.

A phenotype, by contrast, describes what can be observed outwardly, such as symptoms, test results, or clinical presentation.

Understanding endotypes helps explain why people with the same diagnosis can respond differently to treatment. It allows researchers and clinicians to group patients not just by symptoms, but by what is happening in their biology.

This concept is now applied across many fields, including asthma, cancer, autoimmune diseases, and viral infections.

Endotypes in Long Covid

When applied to Long Covid, the endotype concept helps explain why some people recover quickly and others do not.

The Covid Antibody Spectrum Test measures both the quantity and quality of antibodies across several SARS-CoV-2 variants. These data can reveal distinct immune endotypes.

Current evidence suggests approximate proportions:

Hypoimmune (Compromised Response) – ~65%

Hyperimmune (Overactive Response) – ~10%

Universal Response (Balanced Response) – ~25%

These profiles do not represent diagnoses. They offer insight into how the immune system is functioning after infection and support informed discussion about care.

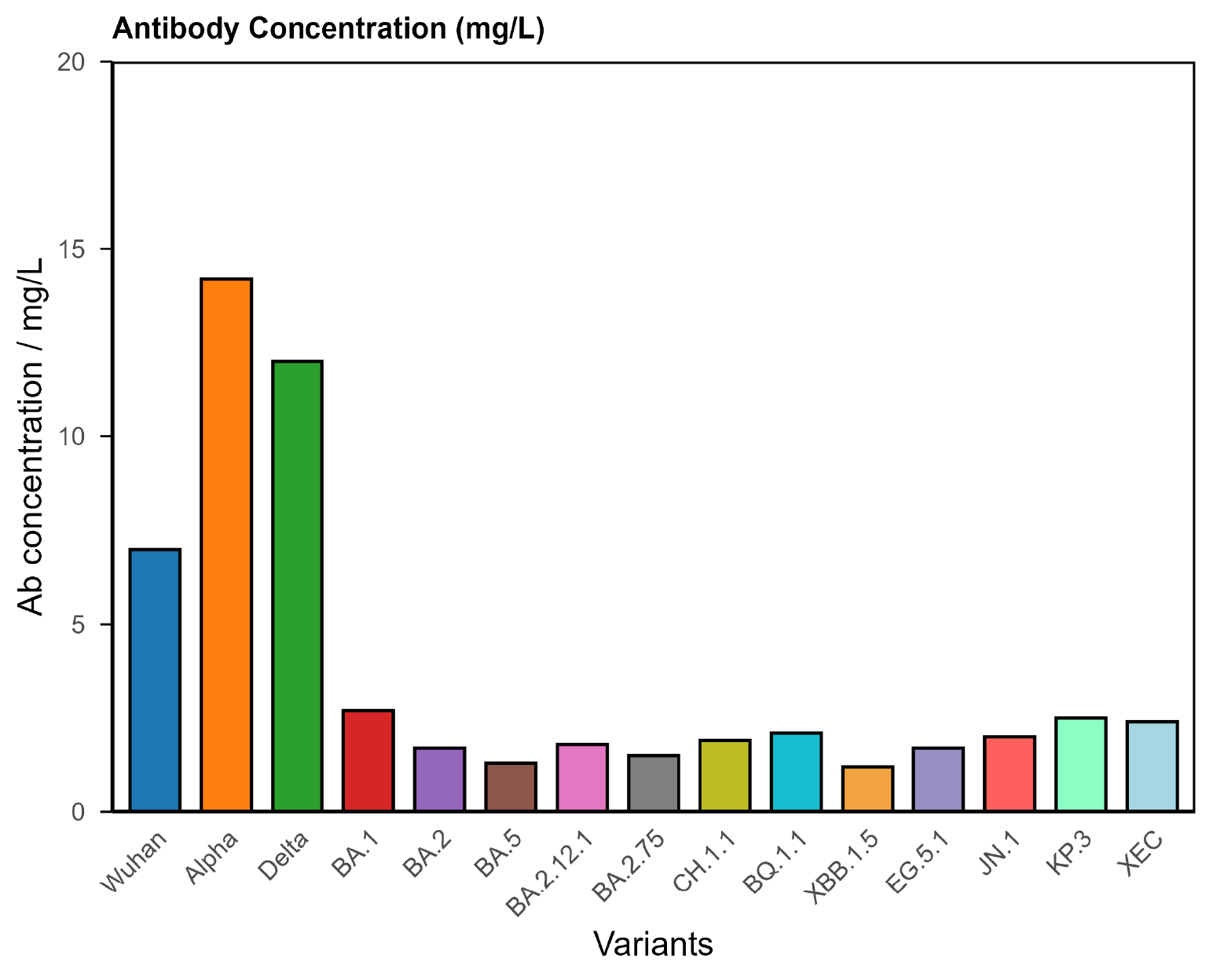

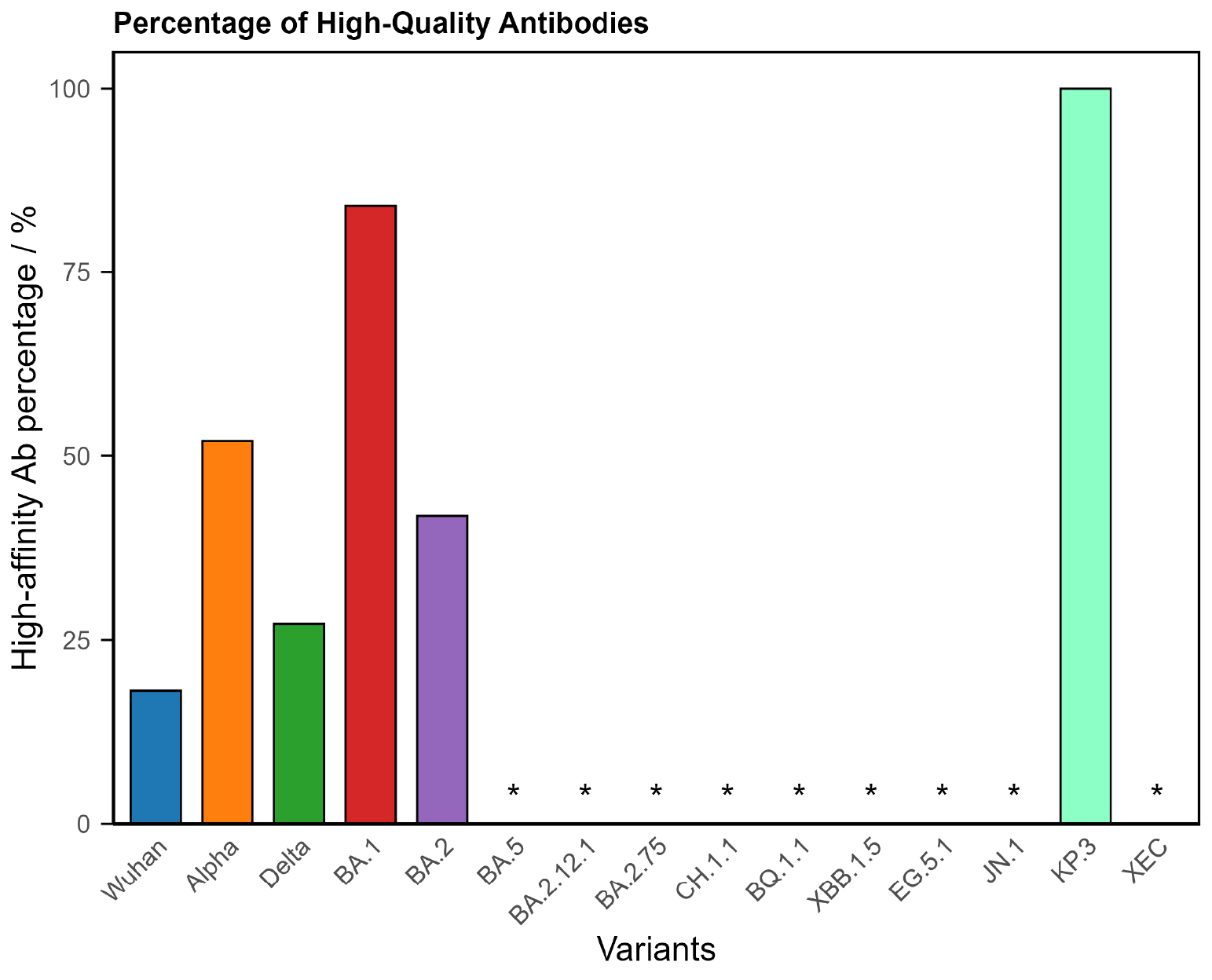

1. Hypoimmune (Compromised Response)

The largest group, representing around two-thirds of Long Covid patients, shows a weaker or incomplete antibody response.

Typical findings

- Low antibody concentrations across multiple variants.

- Poor binding strength (low avidity).

- Narrow breadth of variant coverage.

What this could mean

- Indicates an under-active or incomplete immune response.

- Supports the persistent virus hypothesis, where viral fragments or low-level replication may linger and keep the immune system engaged.

- Helps explain delayed recovery or relapse of symptoms after exertion or exposure.

What this might mean for care or treatment

- Research is exploring strategies to support immune clearance or improve antibody quality.

- Care discussions may focus on reviewing immune status over time and strengthening immune recovery.

- Monitoring and follow-up may be of value for individuals in this group.

Key points

- Represents about ~65 % of Long Covid patients.

- Reflects a low or compromised immune profile.

- Linked with ongoing research into viral persistence.

Figure 1. COVID Antibody Spectrum Test results showing low concentrations and poor antibody quality to multiple variants.

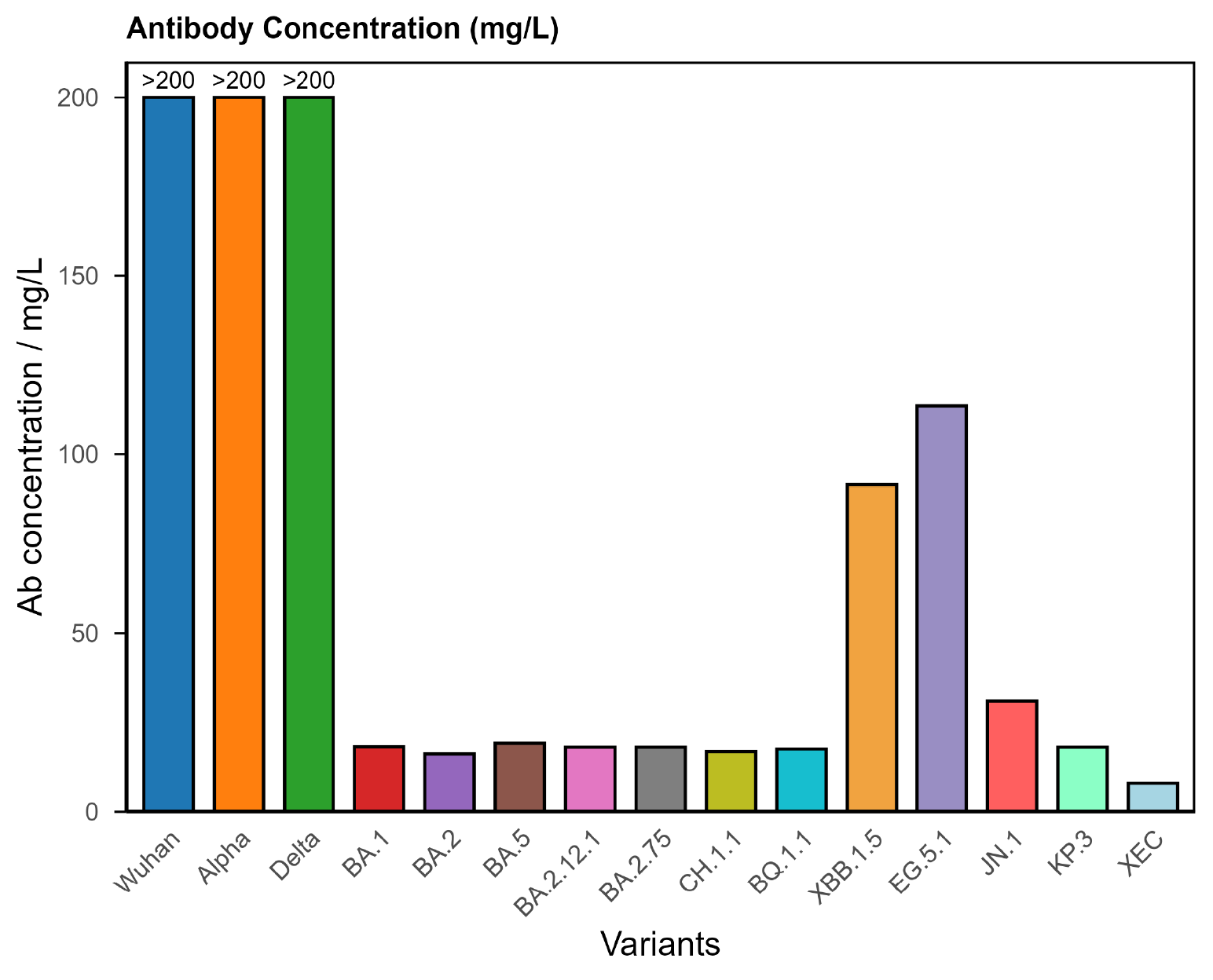

2. Hyperimmune (Overactive Response)

A smaller group, around one in ten patients, shows very high antibody levels across many variants.

Typical findings

- Very high antibody concentrations across most variants.

- Strong binding strength.

- Broad coverage of variants.

What this could mean

- Indicates an immune system that remains highly active long after the initial infection.

- Suggests immune dysregulation rather than continued viral presence.

- May overlap with inflammation or immune-activation pathways beyond the viral antigen.

What this might mean for care or treatment

- Research focuses on restoring immune balance rather than boosting immunity further.

- Care discussions may include ways to reduce persistent immune activation while maintaining protection.

- Monitoring immune markers and symptoms over time may guide decision-making.

Key points

- Represents about ~10 % of Long Covid patients.

- Reflects an overactive immune response.

- Linked with research into immune regulation and resolution.

Figure 2. COVID Antibody Spectrum Test results showing very high concentrations of antibodies to multiple variants, consistent with a hyperimmune response.

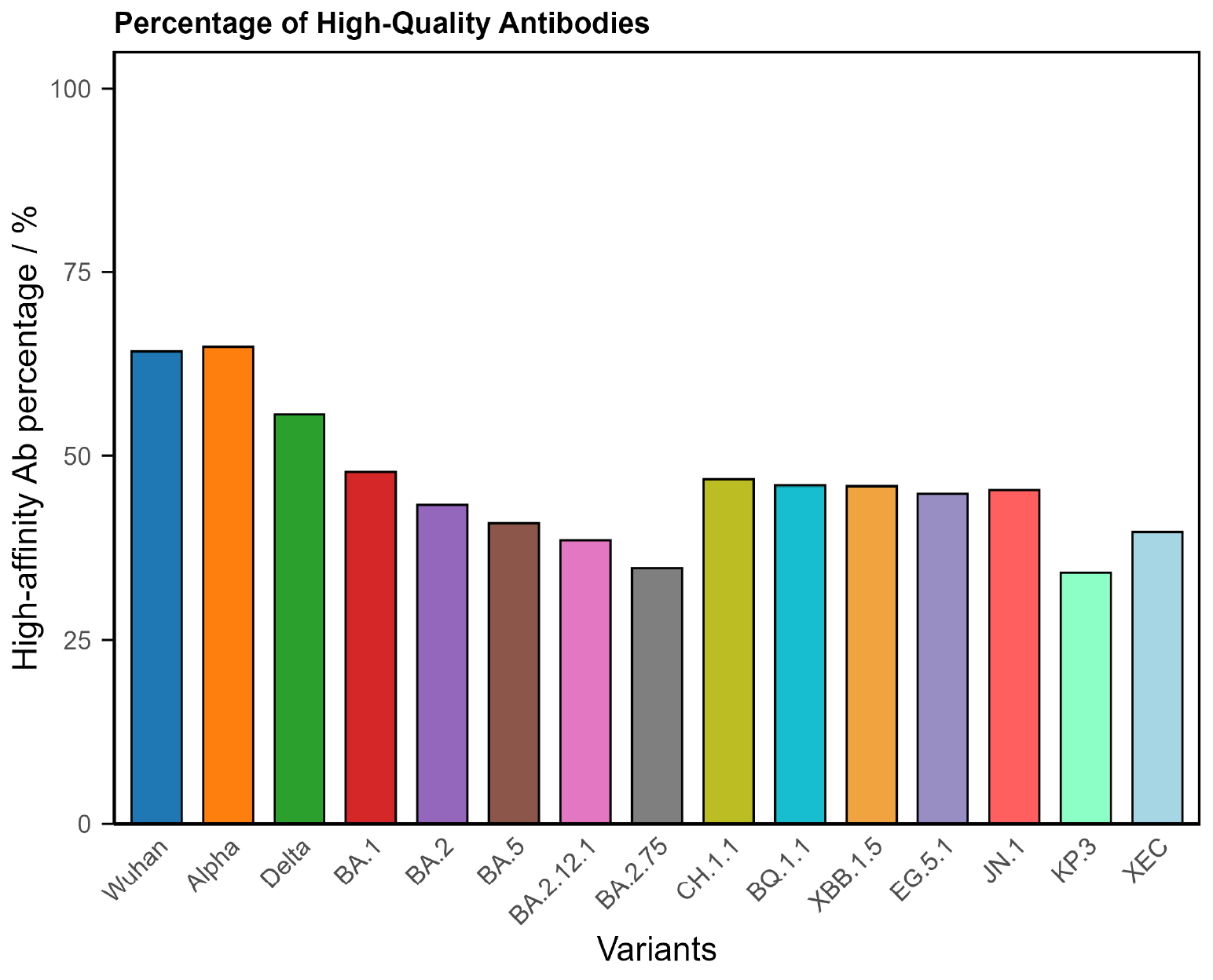

3. Universal Response (Balanced Response)

About one in four Long Covid patients shows a balanced immune profile. Their antibody levels and quality indicate the immune system responded normally, yet symptoms continue.

Typical findings

- Adequate antibody concentrations across all variants.

- High binding quality.

- Broad and even coverage.

What this could mean

- Immune memory appears intact; persistent symptoms are likely driven by other biological systems (neurological, metabolic, vascular).

- Research is examining these non-immune mechanisms of ongoing illness.

What this might mean for care or treatment

- Approaches may focus on rehabilitation, symptom management and body system support rather than immune correction.

- Care discussions may emphasise pacing, sleep, nutrition, and targeted functional recovery.

- Monitoring for stability rather than repeated immune-testing may be appropriate in many cases.

Key points

- Represents about ~25 % of Long Covid patients.

- Reflects a balanced immune profile.

- Suggests involvement of non-immune mechanisms in persistent symptoms.

Figure 3. COVID Antibody Spectrum Test results showing a balanced profile with sufficient antibodies and of sufficient quality to demonstrate a typical immune response.

Why Endotypes Matter

Understanding immune endotypes helps you:

Appreciate biological differences among Long Covid patients.

Engage in informed discussion with your clinician about where your recovery may sit on the spectrum.

Recognise persistent symptoms that could be linked with measurable immune patterns.

In conjunction with your clinician, consider therapeutic approaches and care options that are consistent with your immune profile.

Support ongoing research into therapy strategies that are better matched to biological profiles, not just symptoms.

References

- An, A. Y. et al. “Post-COVID symptoms are associated with endotypes defined by distinct inflammatory and hemostatic responses.” PMC (2023). https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10482103/ PMC

- Davis, H. E. et al. “Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations.” Nature Reviews Microbiology (2023). https://www.nature.com/articles/s41579-022-00846-2 Nature

- Joseph, G. et al. “Persistence of Long COVID Symptoms Two Years After SARS-CoV-2 Infection.” PMC (2024). https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11680455/ PMC

- Peluso, M. J. et al. “Mechanisms of long COVID and the path toward therapeutics.” Cell (2024). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0092867424008869 ScienceDirect+1

- Zuo, W. et al. “The persistence of SARS-CoV-2 in tissues and its implications for Long COVID.” The Lancet Infectious Diseases (2024). https://www.thelancet.com/journals/laninf/article/PIIS1473-3099(24)00171-3/fulltext The Lancet

- Liu, S. “Viral persistence in long COVID: Research advances and implications.” Infectious Diseases (2025). https://journals.lww.com/idi/fulltext/2025/10000/viral_persistence_in_long_covid__research_advances.7.aspx Lippincott Journals

- Kervevan, J. et al. “Divergent adaptive immune responses define two types of Long COVID.” Frontiers in Immunology (2023). https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1221961/full Frontiers

- Guo, L. et al. “Durability and cross-reactive immune memory to SARS-CoV-2 in individuals 2 years after recovery.” The Lancet Microbe (2024). https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanmic/article/PIIS2666-5247(23)00255-0/fulltext The Lancet

COVID Antibody Spectrum Test

Authorised under UKCA

Advanced multiplex test that measures antibody quantity and quality across 15 COVID-19 variants to provide an informative window into the immune system of Long COVID patients, including classification of their endotype into hypoimmune, hyperimmune or universal responder. This can help guide appropriate and personalised therapeutic choices.

Authorised under UKCA

Quantitative measurement of antibody levels

Quantitative assessment of antibody functional quality

Identifies immune subtypes

Supports informed treatment & vaccination decisions